Virus classification

Virus classification involves naming and placing viruses into a taxonomic system. Like the relatively consistent classification systems seen for cellular organisms, virus classification is the subject of ongoing debate and proposals. This is largely due to the pseudo-living nature of viruses, which are not yet definitively living or non-living. As such, they do not fit neatly into the established biological classification system in place for cellular organisms, such as eukaryotes and prokaryotes.

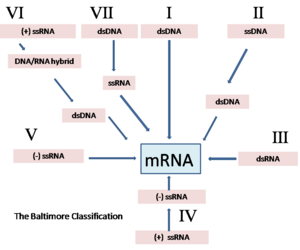

Virus classification is based mainly on phenotypic characteristics, including morphology, nucleic acid type, mode of replication, host organisms, and the type of disease they cause. A combination of two main schemes is currently in widespread use for the classification of viruses. David Baltimore, a Nobel Prize-winning biologist, devised the Baltimore classification system, which places viruses into one of seven groups. These groups are designated by Roman numerals and separate viruses based on their mode of replication, and genome type. Accompanying this broad method of classification are specific naming conventions and further classification guidelines set out by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses.

Contents |

ICTV classification

The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses began to devise and implement rules for the naming and classification of viruses early in the 1990s, an effort that continues to the present day. The ICTV is the only body charged by the International Union of Microbiological Societies (IUMS) with the task of developing, refining, and maintaining a universal virus taxonomy. The system shares many features with the classification system of cellular organisms, such as taxon structure. Viral classification starts at the level of order and follows as thus, with the taxon suffixes given in italics:

So far, six orders have been established by the ICTV: the Caudovirales, Herpesvirales, Mononegavirales, Nidovirales, Picornavirales, and Tymovirales. These orders span viruses with varying host ranges. Caudovirales are tailed dsDNA (group I) bacteriophages, Herpesvirales contains large eukaryotic dsDNA viruses, Mononegavirales includes non-segmented (-) strand ssRNA (Group V) plant and animal viruses, Nidovirales is composed of (+) strand ssRNA (Group IV) viruses with vertebrate hosts, Picornavirales contains small (+) strand ssRNA viruses that infect a variety of plant, insect, and animal hosts, and Tymovirales contains monopartite ssRNA viruses that infect plants. Other variations occur between the orders, for example, Nidovirales are isolated for their differentiation in expressing structural and non-structural proteins separately. However, this system of nomenclature differs from other taxonomic codes on several points. A minor point is that names of orders and families are italicized, as in the ICBN.[1] Most notably, species names generally take the form of [Disease] virus. The establishment of an order is based on the inference that the virus families contained within a single order have most likely evolved from a common ancestor. The majority of virus families remain unplaced. Currently (2009) 6 orders, 87 families, 19 subfamilies, 348 genera, and 2,288 species of virus have been defined[2].

Baltimore classification

Baltimore classification (first defined in 1971) is a classification system that places viruses into one of seven groups depending on a combination of their nucleic acid (DNA or RNA), strandedness (single-stranded or double-stranded), Sense, and method of replication. Other classifications are determined by the disease caused by the virus or its morphology, neither of which are satisfactory due to different viruses either causing the same disease or looking very similar. In addition, viral structures are often difficult to determine under the microscope. Classifying viruses according to their genome means that those in a given category will all behave in a similar fashion, offering some indication of how to proceed with further research. Viruses can be placed in one of the seven following groups:[3]

- I: dsDNA viruses (e.g. Adenoviruses, Herpesviruses, Poxviruses)

- II: ssDNA viruses (+)sense DNA (e.g. Parvoviruses)

- III: dsRNA viruses (e.g. Reoviruses)

- IV: (+)ssRNA viruses (+)sense RNA (e.g. Picornaviruses, Togaviruses)

- V: (−)ssRNA viruses (−)sense RNA (e.g. Orthomyxoviruses, Rhabdoviruses)

- VI: ssRNA-RT viruses (+)sense RNA with DNA intermediate in life-cycle (e.g. Retroviruses)

- VII: dsDNA-RT viruses (e.g. Hepadnaviruses)

DNA viruses

- Group I: viruses possess double-stranded DNA.

- Group II: viruses possess single-stranded DNA.

| Virus Family | Examples (common names) | Virion naked/enveloped |

Capsid Symmetry |

Nucleic acid type | Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Adenoviridae | Adenovirus | Naked | Icosahedral | ds | I |

| 2.Papillomaviridae | Papillomavirus | Naked | Icosahedral | ds circular | I |

| 3.Parvoviridae | Parvovirus B19 | Naked | Icosahedral | ss | II |

| 4.Herpesviridae | Herpes simplex virus, varicella-zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus | Enveloped | Icosahedral | ds | I |

| 5.Poxviridae | Smallpox virus, vaccinia virus | Complex coats | Complex | ds | I |

| 6.Hepadnaviridae | Hepatitis B virus | Enveloped | Icosahedral | circular, partially ds | VII |

| 7.Polyomaviridae | Polyoma virus; JC virus (progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy) | Naked | Icosahedral | ds circular | I |

| 8.Circoviridae | Transfusion Transmitted Virus | Naked | Icosahedral | ss circular | II |

RNA viruses

- Group III: viruses possess double-stranded RNA genomes, e.g. rotavirus. These genomes are always segmented.

- Group IV: viruses possess positive-sense single-stranded RNA genomes. Many well known viruses are found in this group, including the picornaviruses (which is a family of viruses that includes well-known viruses like Hepatitis A virus, enteroviruses, rhinoviruses, poliovirus, and foot-and-mouth virus), SARS virus, hepatitis C virus, yellow fever virus, and rubella virus.

- Group V: viruses possess negative-sense single-stranded RNA genomes. The deadly Ebola and Marburg viruses are well known members of this group, along with influenza virus, measles, mumps and rabies.

| Virus Family | Examples (common names) | Virion naked/enveloped |

Capsid Symmetry |

Nucleic acid type | Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Reoviridae | Reovirus, Rotavirus | Naked | Icosahedral | ds | III |

| 2.Picornaviridae | Enterovirus, Rhinovirus, Hepatovirus, Cardiovirus, Aphthovirus, Poliovirus, Parechovirus, Erbovirus, Kobuvirus, Teschovirus, Coxsackie | Naked | Icosahedral | ss | IV |

| 3.Caliciviridae | Norwalk virus, Hepatitis E virus | Naked | Icosahedral | ss | IV |

| 4.Togaviridae | Rubella virus | Enveloped | Icosahedral | ss | IV |

| 5.Arenaviridae | Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus | Enveloped | Complex | ss(-) | V |

| 6.Flaviviridae | Dengue virus, Hepatitis C virus, Yellow fever virus | Enveloped | Icosahedral | ss | IV |

| 7.Orthomyxoviridae | Influenzavirus A, Influenzavirus B, Influenzavirus C, Isavirus, Thogotovirus | Enveloped | Helical | ss(-) | V |

| 8.Paramyxoviridae | Measles virus, Mumps virus, Respiratory syncytial virus | Enveloped | Helical | ss(-) | V |

| 9.Bunyaviridae | California encephalitis virus, Hantavirus | Enveloped | Helical | ss(-) | V |

| 10.Rhabdoviridae | Rabies virus | Enveloped | Helical | ss(-) | V |

| 11.Filoviridae | Ebola virus, Marburg virus | Enveloped | Helical | ss(-) | V |

| 12.Coronaviridae | Corona virus | Enveloped | Helical | ss | IV |

| 13.Astroviridae | Astrovirus | Naked | Icosahedral | ss | IV |

| 14.Bornaviridae | Borna disease virus | Enveloped | Helical | ss(-) | V |

Reverse transcribing viruses

- Group VI: viruses possess single-stranded RNA genomes and replicate using reverse transcriptase. The retroviruses are included in this group, of which HIV is a member.

- Group VII: viruses possess double-stranded DNA genomes and replicate using reverse transcriptase. The hepatitis B virus can be found in this group.

Holmes classification

Holmes (1948) used Carolus Linnaeus's system of binomial nomenclature to classify viruses into 3 groups under one order, Virales. They are placed as follows:

- Group I: Phaginae (attacks bacteria)

- Group II: Phytophaginae (attacks plants)

- Group III: Zoophaginae (attacks animals)

LHT System of Virus Classification

The LHT System of Virus Classification is based on chemical and physical characters like nucleic acid (DNA or RNA), Symmetry (Helical or Icosahedral or Complex), presence of envelope, diameter of capsid, number of capsomers.[4] This classification was approved by the Provisional Committee on Nomenclature of Virus (PNVC) of the International Association of Microbiological Societies (1962). It is as follows:

- Phylum Vira (divided into 2 subphyla)

-

- Subphylum Deoxyvira (DNA viruses)

-

- Class Deoxybinala (dual symmetry)

-

- Order Urovirales

-

-

- Family Phagoviridae

-

- Class Deoxyhelica (Helical symmetry)

-

- Order Chitovirales

-

-

- Family Poxviridae

-

- Class Deoxycubica (cubical symmetry)

-

- Order Peplovirales

-

-

- Family Herpesviridae (162 capsomeres)

-

- Order Haplovirales (no envelope)

-

-

- Family Iridoviridae (812 capsomeres)

- Family Adenoviridae (252 capsomeres)

- Family Papiloviridae (72 capsomeres)

- Family Paroviridae (32 capsomeres)

- Family Microviridae (12 capsomeres)

-

-

- Subphylum Ribovira (RNA viruses)

-

- Class Ribocubica

-

- Order Togovirales

-

-

- Family Arboviridae

-

- Order Lymovirales

-

-

- Family Napoviridae

- Family Reoviridae

-

- Class Ribohelica

-

- Order Sagovirales

-

-

- Family Stomataviridae

- Family Paramyxoviridae

- Family Myxoviridae

-

- Order Rhabdovirales

-

- Suborder Flexiviridales

-

- Family Mesoviridae

- Family Peptoviridae

- Suborder Rigidovirales

-

- Family Pachyviridae

- Family Protoviridae

- Family Polichoviridae

Subviral agents

The following agents are smaller than viruses but have some of their properties.

Viroids

- Family Pospiviroidae[5]

- Genus Pospiviroid; type species: Potato spindle tuber viroid

- Genus Hostuviroid; type species: Hop stunt viroid

- Genus Cocadviroid; type species: Coconut cadang-cadang viroid

- Genus Apscaviroid; type species: Apple scar skin viroid

- Genus Coleviroid; type species: Coleus blumei viroid 1

- Family Avsunviroidae[6]

- Genus Avsunviroid; type species: Avocado sunblotch viroid

- Genus Pelamoviroid; type species: Peach latent mosaic viroid

Satellites

Satellites depend on co-infection of a host cell with a helper virus for productive multiplication. Their nucleic acids have substantially distinct nucleotide sequences from either their helper virus or host. When a satellite subviral agent encodes the coat protein in which it is encapsulated, it's then called a satellite virus.

- Satellite viruses[7]

- Single-stranded RNA satellite viruses

- Subgroup 1: Chronic bee-paralysis satellite virus

- Subgroup 2: Tobacco necrosis satellite virus

- Single-stranded RNA satellite viruses

- Satellite nucleic acids

- Single-stranded satellite DNAs

- Double-stranded satellite RNAs

- Single-stranded satellite RNAs

- Subgroup 1: Large satellite RNAs

- Subgroup 2: Small linear satellite RNAs

- Subgroup 3: Circular satellite RNAs (virusoids)

Prions

Prions, named for their description as "proteinaceous and infectious particles," lack any detectable (as of 2002) nucleic acids or virus-like particles. They resist inactivation procedures that normally affect nucleic acids.[8]

- Mammalian prions:

- Agents of spongiform encephalopathies

- Fungal prions:

- PSI+ prion of Saccharomyces cerevisiae

- URE3 prion of Saccharomyces cerevisiae

- RNQ/PIN+ prion of Saccharomyces cerevisiae

- Het-s prion of Podospora anserina

Notes

- ↑ The Virus Species Concept: Introduction Virus Taxonomy Online: Seventh Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. 2000. Retrieved on 2007-07-14.

- ↑ ICTV Virus Taxonomy 2009

- ↑ "Baltimore Classification of Viruses" (Website.) Molecular Biology Web Book - http://web-books.com/. Retrieved on 2008-08-18.

- ↑ Lwoff A, Horne R, Tournier P (1962). "A system of viruses". Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 27: 51–5. PMID 13931895.

- ↑ "80.001 Popsiviroidae - ICTVdB Index of Viruses." (Website.) U.S. National Institutes of Health website. Retrieved on 2007-09-27.

- ↑ "80.002 Avsunviroidae - ICTVdB Index of Viruses." (Website.) U.S. National Institutes of Health website. Retrieved on 2007-09-27.

- ↑ "81. Satellites - ICTVdB Index of Viruses." (Website.) U.S. National Institutes of Health website. Retrieved on 2007-09-27.

- ↑ "90. Prions - ICTVdB Index of Viruses." (Website.) U.S. National Institutes of Health website. Retrieved on 2007-09-27.

See also

- Binomial nomenclature

- International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses

- List of viruses

- Nomenclature Codes

- Scientific classification

- Taxonomy

- Trinomial nomenclature

- Virology

- List of genera of viruses

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||